I’m pleased to announce that Summer 2022 Part 1 has been selected for the Calderdale Open 2025.

The exhibition takes place at the Smith Art Gallery, Halifax Road, Brighouse, Yorkshire, from the 5th July – 6th December 2025.

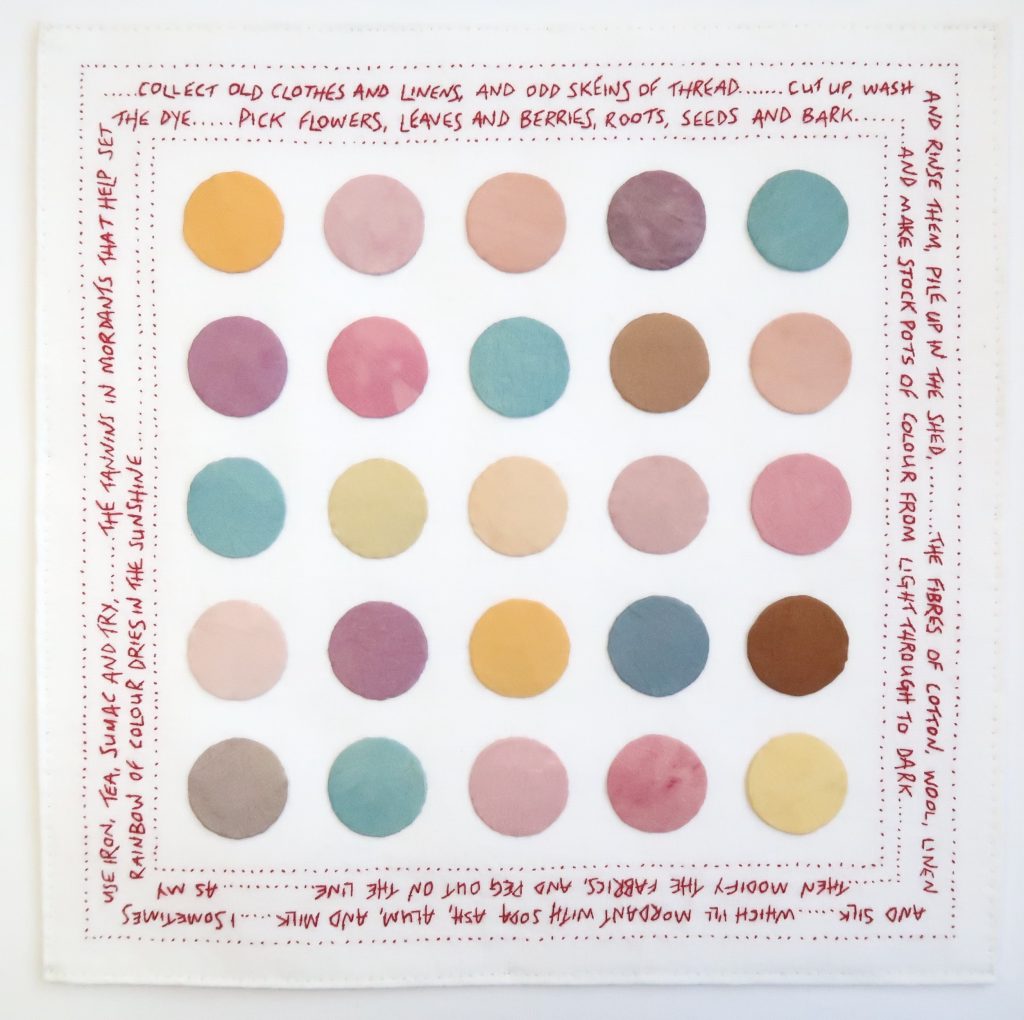

Summer 2022 Part 1

In September 2022 I was invited to an art event at Touchstones Rochdale and took the opportunity to record the thoughts and memories of the people of Rochdale about how they had been affected by the summers’s heatwave.

When I returned home I realised I had enough information to create two artworks – ‘Summer 2022 Part 1 & 2’. These pieces document how everyday lives were afected by the extreme heat, lack of water and the war in Ukraine.

The artworks cover a timeframe from mid-summer through to the 10th September 2022 with the death of HM Queen Elizabeth II.

Calderdale Open Judges

Kate Lycett – “My textile design background is always present in the way that I paint, and interpret what is around me. I see patterns in everything; the hills adorned with houses and washing lines, rows of flower pots and stripes of brightly painted drain pipes. Lines of gold thread trace lines through the landscape, and gold leaf changes the surface of my pictures with the changing light of day. I want to paint beautiful pictures of the places that I love. There are never people in my pictures but they’re full of life and warmth.”

Associate Professor Dr Marianna Tsionki – University Curator at Leeds Arts University heading up the Curation and Library department. She is responsible for strategic and operational planning of libraries and curatorial programmes, collections management and research development……Marianna is a curator, researcher and educator working at the intersection of contemporary art, ecology and technology. She is concerned with the role of curatorial and institutional practice in a time of ecological crisis, with particular focus on methodologies of alter-institutionality and critical pedagogy.

Mike Baggs AC Art & Framing – “AC Gallery began life as an art shop in the 1950’s and is now in the 3rd generation of the same family. The business has evolved over the decades, from its early days as an arts and crafts supply shop, to the AC Gallery we have today selling framed prints and originals alongside our expert picture framing service… Now with seven galleries across the north, it’s a long way from the art shop of the 1950’s but the core values have never changed. We are a family business where every customer and every job matters.”

Thank you to curator Eli Dawson and the judges for selecting my work for the exhibition.